The Story of Exeter

A few feet astern followed the youth of Exeter, decorated with a crimson scarf, in a cutter of dazzling white, and impelled by the same number of oars.

The Episcopal Watchman, 1828

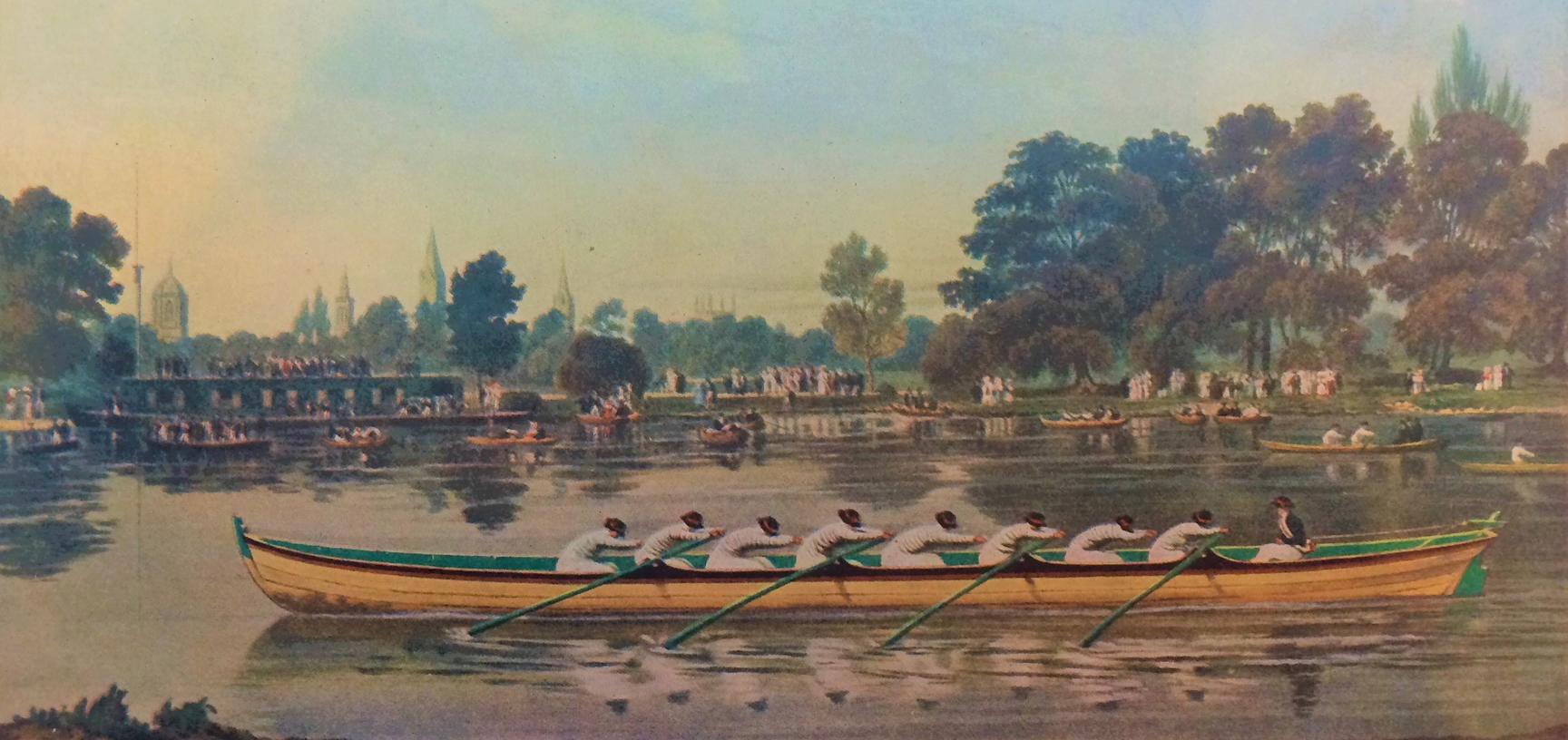

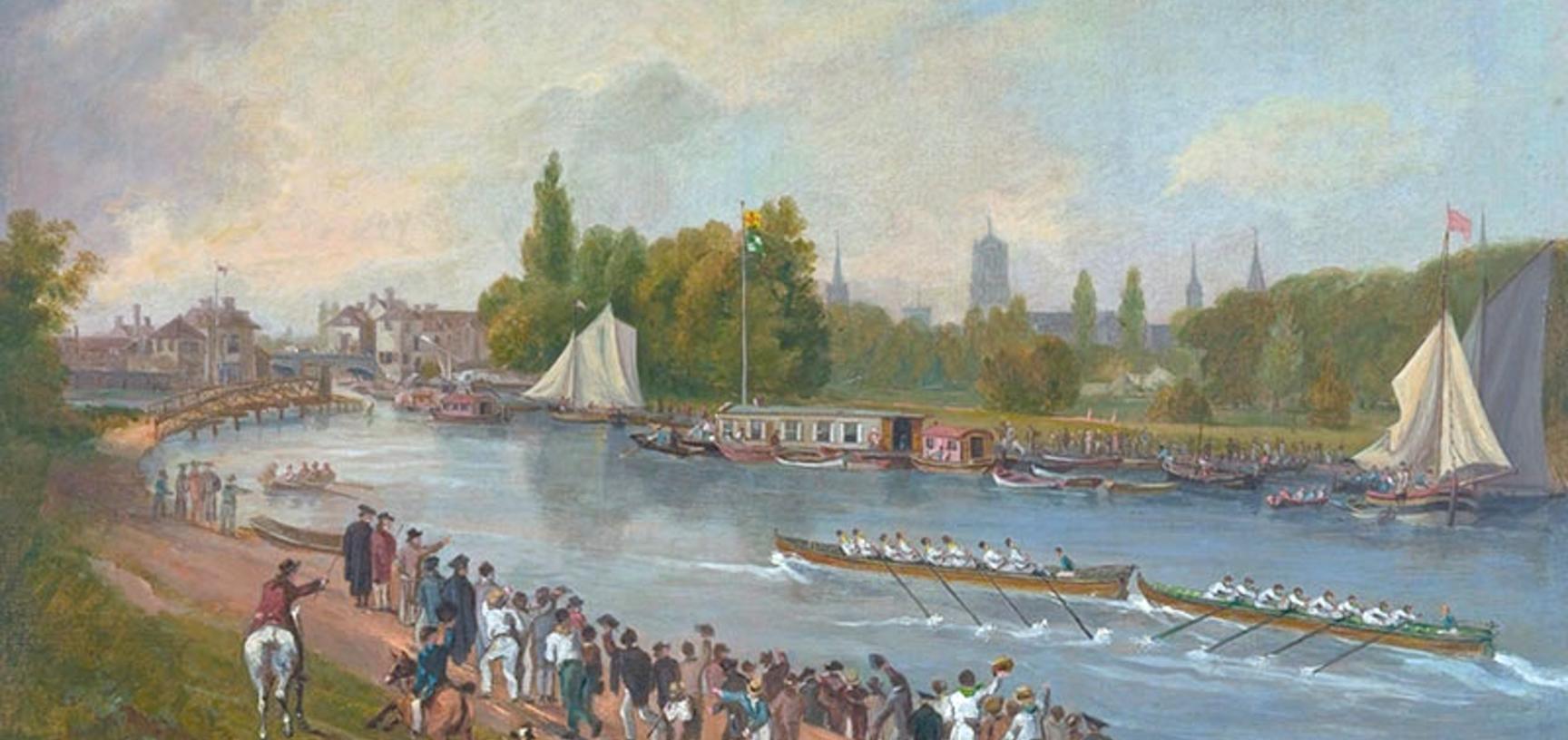

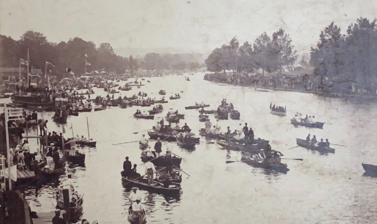

Bumps racing in Oxford began in 1815, when boats from Jesus and Brasenose raced each other home following an excursion to Iffley lock. The narrow width of the Isis forced the two crews to race behind one another, rather than side-by-side. Brasenose won the first race, and retained their title the following year.

(An amusing fact about Exeter’s Turl Street rival: Jesus men’s second-placed finishes in 1815 and 1816 remain their highest-ever position on the river.)

The club was founded in 1823 by Henry Bulteel, whom contemporaries described as a fearsome individual. Bulteel, who was a fellow at Exeter, only had one eye (the other having been knocked out during a cricket match at Eton), and was known for inciting religious riots in Oxford over the king’s divorce.

Exeter completed the quartet of ancient Oxford boat clubs with the adoption of red blades, following Brasenose (black), Jesus (green), and Christ Church (blue – formed in 1817).

Exeter became Head of the River in their maiden year, bumping all crews on their way to the top in 1824.

Non-appearance in Chapel was held tantamount to ejection from the crew.

The Captain’s Book, 1869

Exeter this year achieved a success which is probably without precedent in the annals of rowing at Oxford, by going from fourth to head of the river with a crew comprising six Torpid men and one who had not even rowed in the Torpid.

The Captain’s Book, 1882

The decades following Exeter’s foundation saw the club rise to the summit of English rowing.

In 1839, the increasing popularity of rowing led to the creation of an event for second boats. The name of this new regatta – the Torpids – was a brass-necked reference to the speed of the participants. Exeter participated in the first Torpids, and would proceed to win thirteen of the first thirty editions.

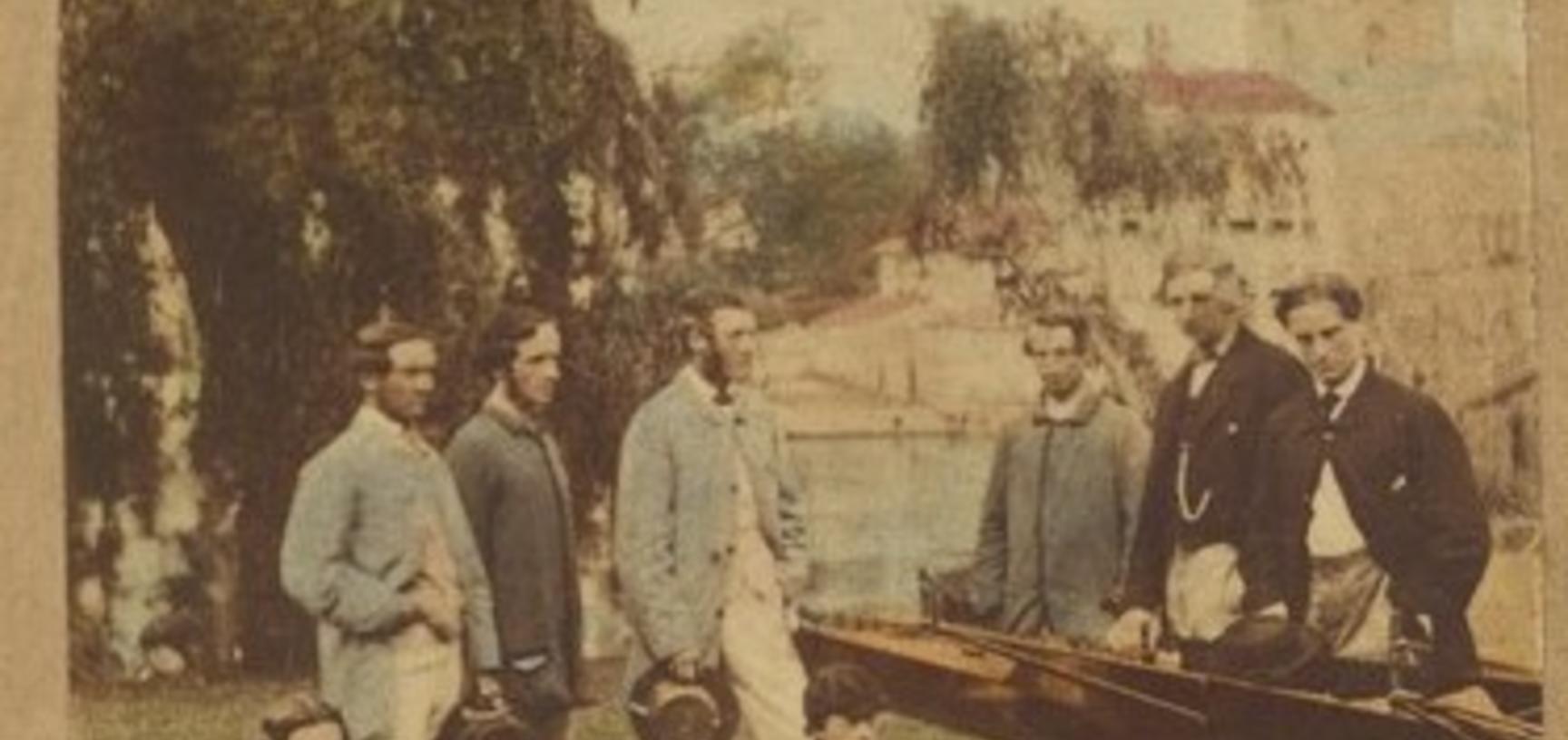

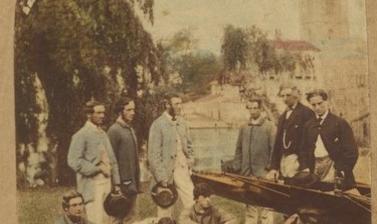

Several famous rowers were members of the club in the 19th century. There was Frank Willan, who won four consecutive Boat Races (1866-1869) and was an early proponent of the bow ball. Another was Richard ‘Dick’ Kindersley, a three-time Boat Race winner, who was a giant for the time at 14st and 6ft3in. He also won blues for rugby and boxing, and was capped by England for rugby. A disputed try by Kindersley in 1884 led to the creation of the International Rugby Board, now World Rugby.

Exeter led some impressive campaigns in this period to claim headship in Eights. By far the most impressive was in 1882, when a heavy underdog crew made up of Torpids rowers bumped Brasenose, Hertford, and Magdalen to become Head of the River. The club retained headship comfortably for the next two years, before losing out to a monstrous Corpus Christi crew. 1884 remains Exeter’s most recent headship.

He is about the ugliest stroke on the river, yet manages to hustle along at a good pace.

The Times describes the St John’s stroke-man catching Exeter, 1872

Oxbridge colleges are not typically successful at Henley Royal Regatta today: the most recent club to win an event was First and Third of Trinity (Cambridge) in 1967.

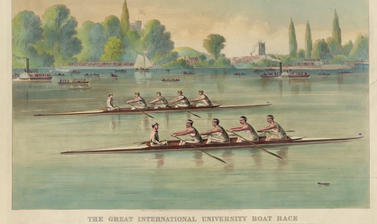

Circumstances could not have been more different in the 19th century when every competition was dominated by colleges. Exeter was among them, winning the Silver Goblets pairs competition in 1851 and the Ladies’ Challenge Plate for intermediate eights in 1857.

Exeter’s most spectacular victory, however, was achieved in 1882. The first eight, fresh from winning headship in Oxford and bolstered by the return of two Blues, entered the Grand Challenge Cup – the premier event at the regatta, contested today by Olympic crews. In the final, they defeated Thames Rowing Club by a margin that remains one of the largest in the Grand’s history.

Other years were not so glorious. In the 19th century, Oxford clubs rowed their boats the entire 50 miles to Henley, which could present problems. In 1858, Exeter’s boat faced thunderstorms and a crew-wide outbreak of diarrhoea that led to two rowers collapsing from exhaustion. They were heavily defeated in the first heat and had to immediately make the long journey home.

3. For the duration of the war, the E.C.B.C. and Lincoln B.C. have been combined, and this joint boat club will be run by an acting committee.

The emergency constitution, 1939

The start of the First World War just before the 1914-15 academic year cancelled all events as a huge number of rowers volunteered for service. By 1919 there had been a shocking toll on the boat club. The two most recent captains had been killed, as had more than half of the 1914 torpid.

There had been too much disruption for the university to run bumps racing as normal in 1919. A one-off event was held instead, in which results did not count towards the overall bumps charts; Exeter put out a joint boat with University College for this regatta. Normal racing resumed with Torpids in 1920.

Exeter was better prepared for the outbreak of hostilities in 1939. The club merged with its neighbour, Lincoln, for the duration of the war, with Corpus Christi and St Peter’s also providing rowers. Racing was shortened as colleges merged, and the rapid turnover in club membership (owing to conscription and redeployment) meant that results did not affect the 1939 order of start. Historical positions were restored in 1946.

The club lost thirteen members (including two captains) in the Second World War, but the sense of optimism was greater in 1945 than in 1918. Exeter and Lincoln held a joint celebration dinner before parting ways, during which there were raucous toasts and sharing of fond memories from the last six years.

The visitors were welcomed with extraordinary kindness and hospitality, being received by H.H. King Haakon at his country house

The Field, 1925

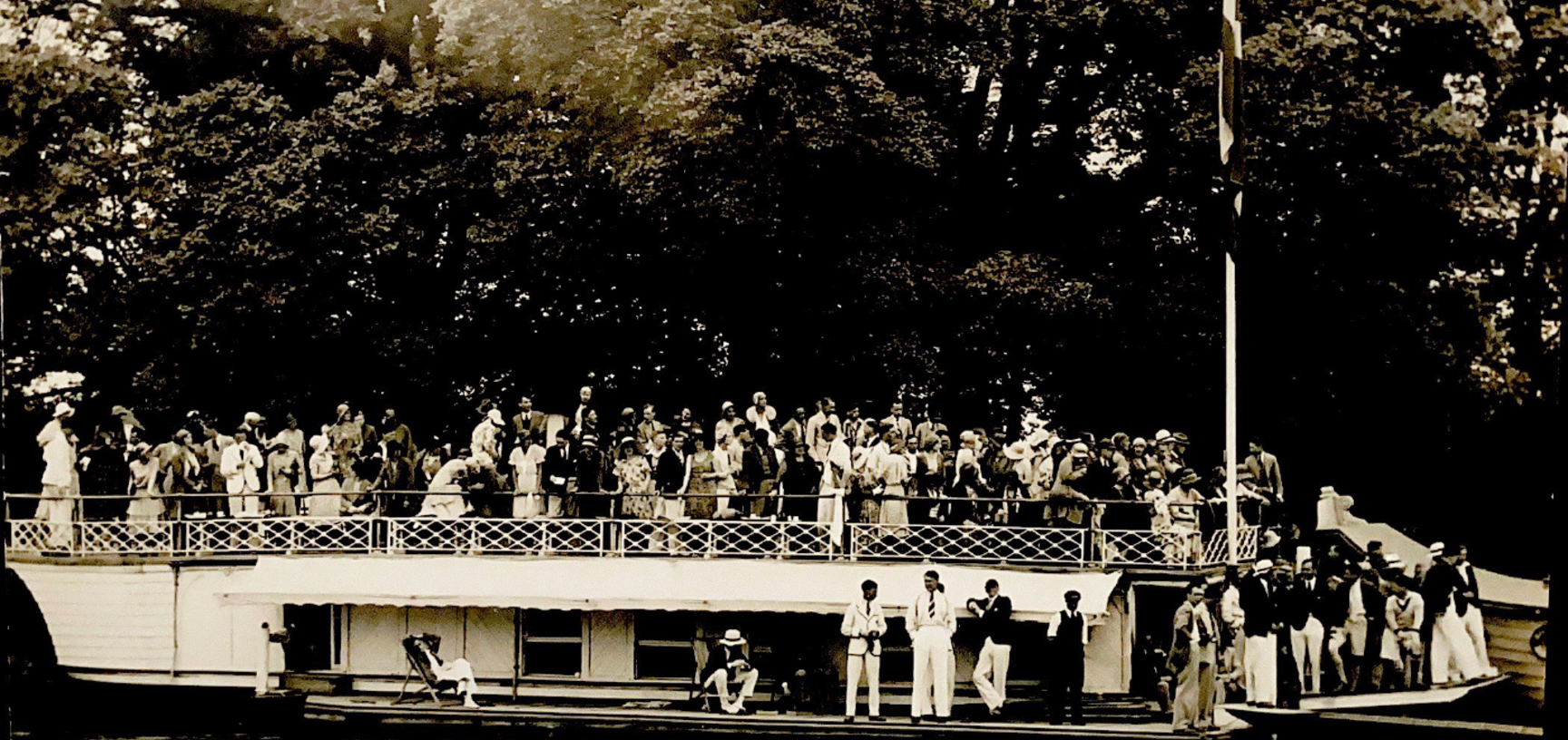

Between the wars, Exeter’s members mixed with royalty and stars of the rowing world.

Prince Hirohito

In 1921, the college barge played host to Crown Prince Hirohito of Japan. Hirohito, who would become Emperor in 1926, was on a tour of Europe over the summer. Between political summits in London and Edinburgh, his party stopped at Oxford, where Eights Week was taking place.

The Vice Chancellor at the time was Lewis Richard Farnell, an ex-Rector of Exeter, who chose his college as the Crown Prince’s host on the river. Farnell was given the duty of firing the starting pistol, but appears to have been a peril with the weapon. The Captain’s Book records how:

It is doubtful how far Prince Hirohito […] did not consider the revolver as a menace to the crew rather than as an encouragement.

Following the visit, the Japanese gifted a gold medal, depicting the imperial seal, to the boat club.

King Haakon

The Norwegian Rowing Association marked its jubilee in 1925, and invited several crews to Christiania (Oslo) for a celebratory regatta. Balliol was the first choice for an English crew, given that Prince Olav was studying there. However, Balliol was only able to collect two rowers, and turned to Exeter for help.

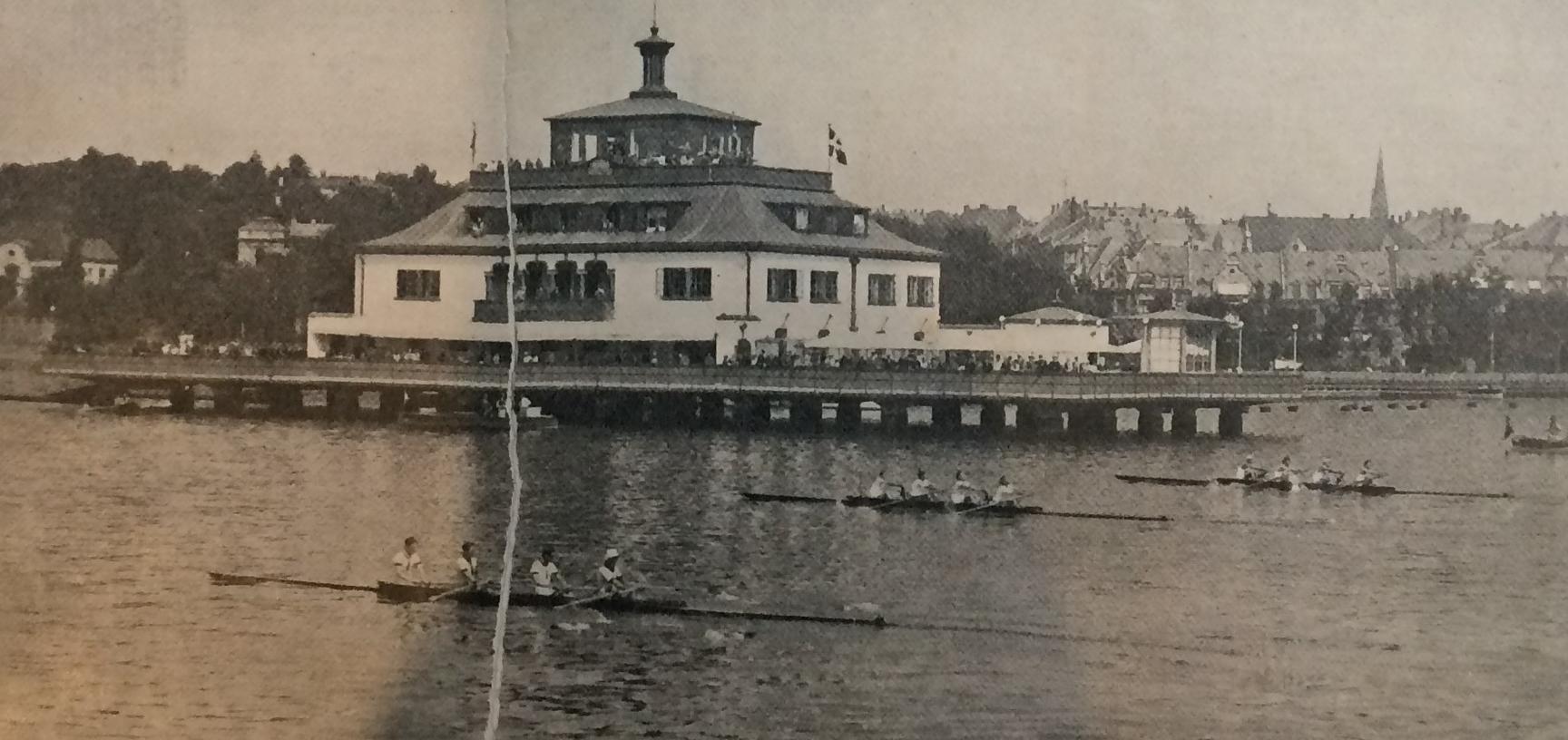

The race took place in coxless fours against crews from Kobenhavns Roklub of Denmark and Christiania Roklub of Norway. The venue was to be the brutal Frogner Fjord, which was hundreds of metres wide and completely open to the elements. The Exeter/Balliol boat was in front at the halfway point, but a crab caught by a Balliol rower saw them finish two lengths behind the Danish victors. Afterwards, King Haakon received the crew warmly at his country house and hosted a dinner in their honour.

Balliol continued its association with the Norwegian royal family, educating Olav’s son – the present King Harald V – in the 1960s. Exeter improved its position on the river, rising to a peak of third in 1929.

Steve Fairbairn

In the build-up to Eights in 1927, Exeter was coached on the Tideway by Steve Fairbairn. Fairbairn’s influence on modern rowing is incomparable; he invented the modern technique involving a more fluid style and heavy use of the legs. At the time, however, many rowers were disdainful of the Australian, deriding his style as the “Fairbairn heresy”.

Fairbairn had been invited to Exeter on the initiative of one of its members, Stamberg, who was promptly nicknamed "Bottles" by Fairbairn on account of the empty beer bottles lining his window sill.

Sadly, Fairbairn was not impressed by Exeter’s performance during Eights Week. He wrote in the student newspaper:

Yet among this year’s Eights I saw only two crews using their legs; Exeter was not one of them: they have picked up the fads but not the virtues of Fairbairnism.

The Captain and the Secretary celebrated the reopening of the college bar before canvassing new members but were nonetheless quite successful. […] At the general meeting the Captain announced a programme of blood sweat and tears which so far has not frightened too many away.

The Captain’s Book, 1949

Change was in the air after the Second World War, as rowing in Oxford started to take on the shape it retains today. Exeter’s leaky barge was replaced in the 1950s by a boat house; gradually, all colleges would make the same change. The building today is currently shared with Brasenose.

The most notable change came in 1976 with the introduction of women’s racing. Exeter’s first women’s eight entered the 1980 regatta, and soon made a big impact, rising from the 5th to the 2nd division within ten years. The women reached the 1st division in Torpids for the first time in 2011. More blues have emerged from the women’s squad than the men’s since 1980, including three-time Boat Race winner Lauren Kedar.

Exeter’s men have continued their mercurial performances. Two impressive periods in the 1970s and 1990s saw them nearly reach headship – in the 2003 Torpids, coming within a foot of Oriel. Between 1992 and 2004, the men’s first boat went 48 days un-bumped, a club record that took them from 27th to 3rd on the river in Eights.

By Matthew Holyoak, ECBCA Chairman

With thanks to Anu Dudhia of the Department of Physics. All pictures published with the permission of the Rector and Scholars of Exeter College, Oxford.